First, before I present some actual arguments, I'd like to point out what I think are the biases prevalent before us (content warning, some mild nudity and, of course, lots of cussing):

I think, somewhat obviously, we have an inflated view of our own preferences and our own past. And, honestly, I think this is what is going on when people say 'music these days sucks'. True, you'll have the gangsta rappers doing there rendition of (yet another content warning, excessive cussing):

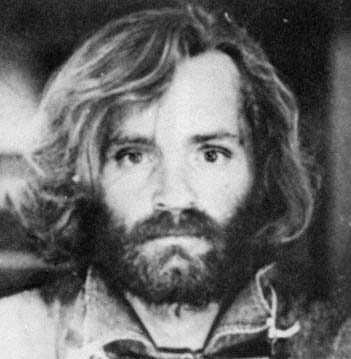

Among other songs very similar. But hey, remember this guy?

My point isn't that Helter Skelter was a worse song, but rather that every harvest has some bad apples Moreover, to be honest, the discussion of absurd content or 'moral quality' is really a red herring. I feel I should note that the moral quality or the strong content of a song is not necessarily linked with the aesthetic quality of a song. To give an example, my father has a copy of Picasso's Blue Guitarist:

It's kept, hidden away, in the back of his garage. I asked him why he keeps a Picasso, even though it may not be original, stuffed in the back of his garage. And he replied, "Look at it." And, when I look at this painting, I can see why you might not want to have it hanging in the middle of your living room for you to look at every day. Now, does the fact that we don't want to look at it indicative that the painting is a bad painting? I would argue for quite the opposite. Since, in order to have that profound of an emotional reaction is indicative of some high quality artwork.

Another example (content warning):

Click here to go to the painting Saturn Devouring His Son

This is a very classical painting. It is also one of the most grotesque paintings I've ever seen and I can't stand to look at it. To me, that's indicative of high quality artwork, even though I personally hate the painting.

With that said, another one of my points to put alongside the fact that we have biases to what we have accumulated experiences to, is that modern music--by nature of its modernity--will strike at themes overtly which making older generations uncomfortable. My point, however, is that there should be a 'Hume's Guillotine of aesthetics,' if you will.

Now, that I've gone over some common logical fallacies and preconceptions I feel I've faced in hearing such arguments, allow me to give at least one actual argument (which, as usual, is the smallest part of my post). And, like any good discussion, I'll quote Chomsky (this one actually is SFW):

(the full interview is fascinating, but I post this segment here regarding the cognitive development and argument for progression in music)

My argument that there is progression in music is basically lifted and copied directly from Chomsky in the above video. The brain has this unique ability of a musical apparatus, the brain cerebrates at a high level when using this apparatus, and moreover, we can communicate various emotional intonations to others using it. The notion of communication is key, and just like how communication of ideas begets intellectual progress. I would posit the same for music.

As some evidence of this claim, I would suggest the reader to go back and start listening to a bunch of classical music; and, I hope you'll find (as I certainly did) how:

-Many of these same themes encountered in classical music--the counterpoint, matching harmonies, or even directly copied passages (the modern remix of Beethoven's Fifth comes to mind)--comes up in later music.

--This, of course, isn't simply limited to classical music. The jazz of the 1920's can be traced back to the Creole music of New Orleans prior to that.

-How often this music is directly used in canon.

As an example of the later point, I'd like to point out the following piece (SFW):

I am convinced you've actually heard this piece before. This is a very common piece to hear in a movie, usually when the protaganist is whistful and there's snow falling.

To back this up, I'll end with the following, listen to the background at 2:25:45 :

The evidence of the use of old themes, and the continual progression and building that we do upon them is ever present if we choose to notice it.

No comments:

Post a Comment